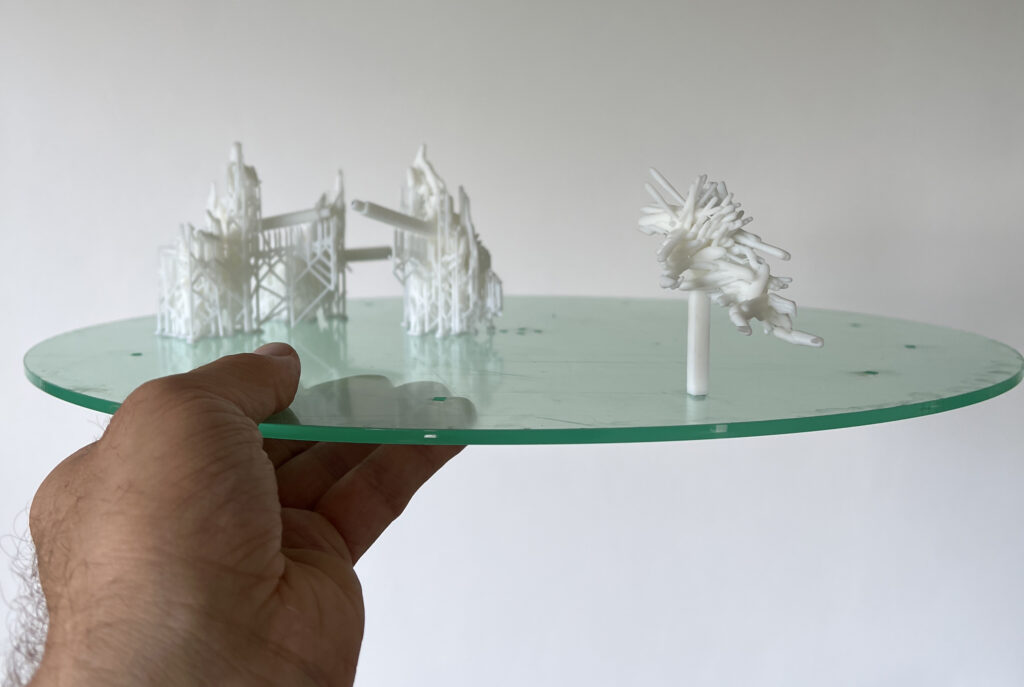

Since I always forsaw a 3D printed version of the installation, the second phase of the Film EU RIT project gave me the opportunity to do just that.

The image above depicts a test 3D print, printed with a resin printer. To test the anamophic shadow effect of the walking figure in real life. It very much matched the VR version of that frame.

Like the VR version, I went for the zoetrope fromat, as this 3D printed version perfectly translated to this medium. In a way I was remixing a concept my colleague Guido Devadder was exploring before for the Expanded Memories project.

This time all the frames were 3D pinted, but were too delicate to remove the supports and many broke.

To remove the variable of removing the supports from the prints an SLS printer was used. The frames turned out much better, but at a higher cost.

Other parts, like the wooden casing, wooden and plexiglass plate were cut with a lasercutter.

I repurposed an old recordplayer, so there was no need to use a stepper motor.

I used a old carboard tube as the centre cylinder that holds up transparant zoetrope platter and the wooden projection plate so the animated shadows could get projected on it.

Using a cellphone led, I tested the assembled installation. This can be done with an app called ‘Stroboscope’ that adjust video shutter speed to created the correct flicker effect to view analogue protoanimation devices like this. Bellow is a video of this test.

The video below is a short edit of footage captured with a camera capable of altering its frame rate. The footage was shot at 12 frames per second using an analog and macro lens on an EOS 60D.

Anamorphotrope V03

For future exhibitions, I have been developing new components for the installation. Apart from the 3D-printed animation frames, the prototype was primarily constructed from cardboard and wood. These materials were light and easily adjustable but had the significant drawback of not being very sturdy. The parts can only be assembled and disassembled a limited number of times before showing signs of wear and tear.

The new components were designed using the Shapr3D software on the iPad, which is well-suited for creating precise, 3D-printable mechanical parts.

The parts are showcased in this short video. I will post updates on the progress of the new installations once they are constructed.